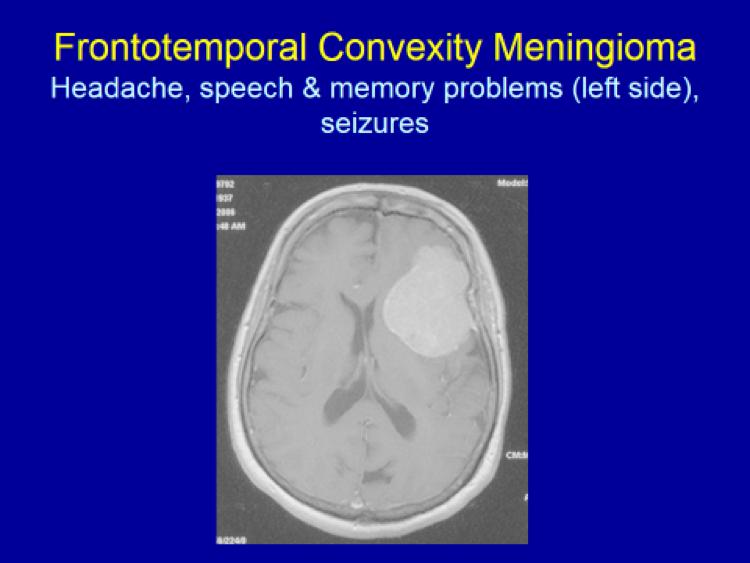

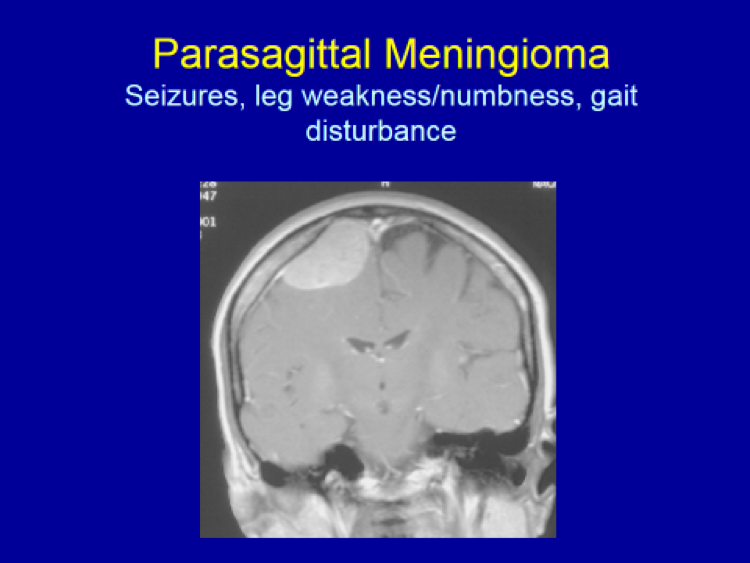

Diagnosing symptomatic meningiomas: Brain MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) is the gold standard for diagnosing intracranial meningiomas. Usually, when patients develop any neurological symptoms – such as headaches, speech problems, seizures, memory loss, body/extremity numbness or weakness, hearing loss, visual loss, double vision, dizziness, imbalance, etc. – a brain imaging is ordered by the patient’s PCP (primary care physician). Preferably, when a brain tumor is suspected, MRI with and without Godolinium (contrast injected intravenously) is performed.

When patients have any metal implants in the body such as cardiac pacemaker, MRI cannot be done. Rather, a brain CT with and without IV contrast is performed. CT is also done as an adjunct to the brain MRI when the meningioma extends into the surrounding skull or the skull base to better delineate the full extent of the tumor including the extent of bone invasion.

When meningiomas are adjacent to or involving the major venous structures, such as the sagittal sinus, torcular, transverse sinus or sigmoid sinus, MRV (Magnetic Resonance Venogram) may be performed additionally to better assess the full extent of the meningioma’s invasion into the surrounding venous structure(s).

When a very vascular meningioma (i.e. rich in blood supply) is suspected based on the preoperative MR imaging, a cerebral angiography may be performed to visualize the full extent of the blood supply to the meningioma as a part of preoperative planning. When it would be deemed appropriate and beneficial, at the same time as the cerebral angiography is being done, tumor embolization may be performed to occlude the feeding blood vessels which, in turn, will make the subsequent surgery less bloody and risky.

Diagnosing asymptomatic, or “incidental”, meningiomas: These days, with the widespread availability and use of brain imaging (either CT or MRI) for evaluating head trauma, nasal sinus complaints or nonspecific neurological complaints, incidental meningiomas (i.e. those detected by an “accident” or not causing any specific symptoms referable to the tumor) are being diagnosed with increasing frequency. When a non-contrast CT done initially to evaluate nasal sinusitis or minor head trauma, for example, reveals a possible meningioma, a brain MRI with and without Gadolinium is ordered to confirm and better delineate the tumor.

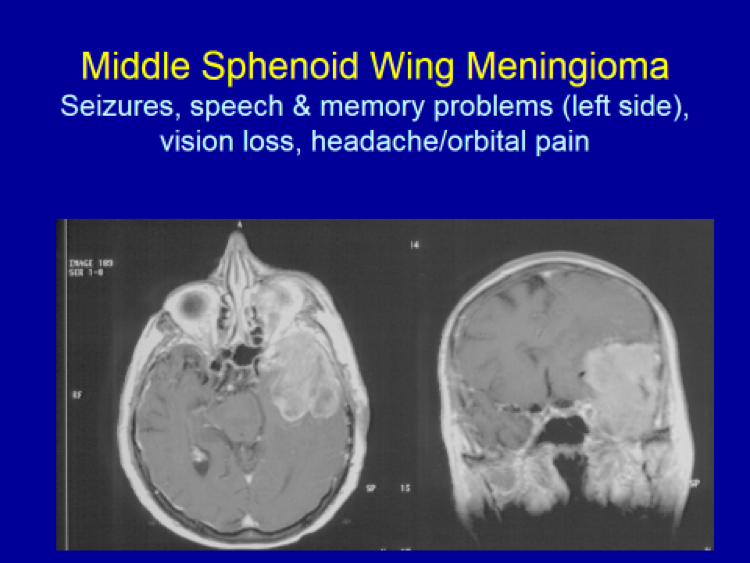

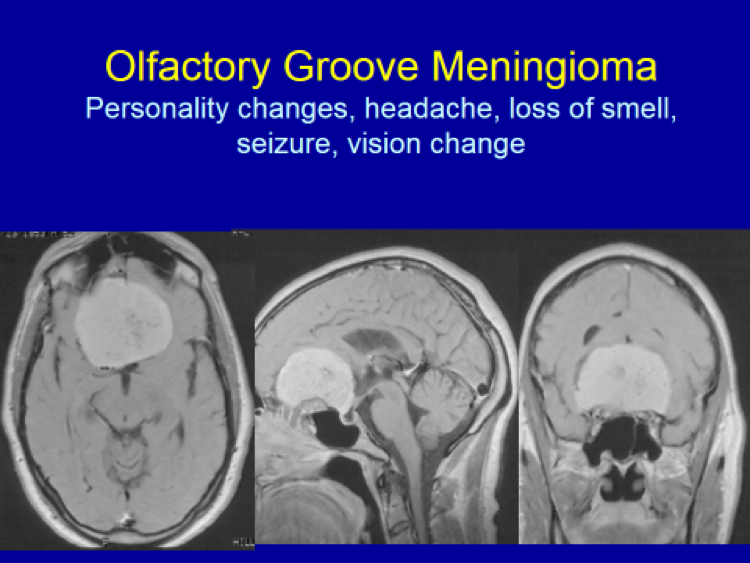

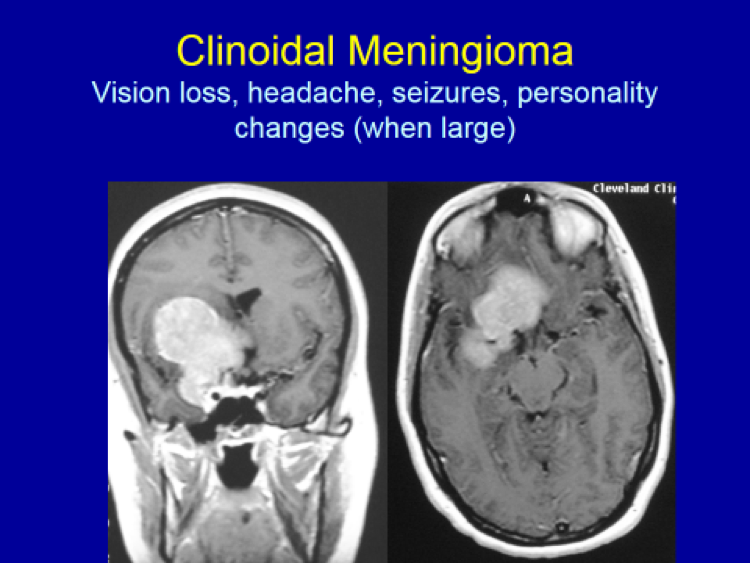

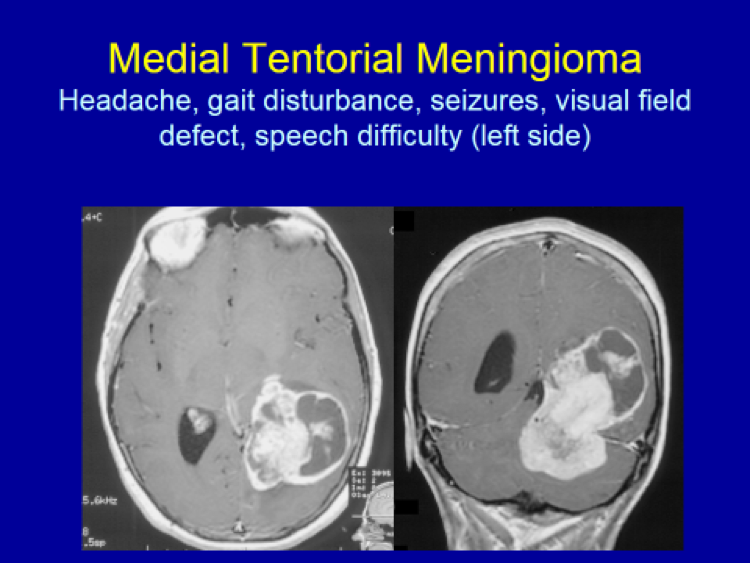

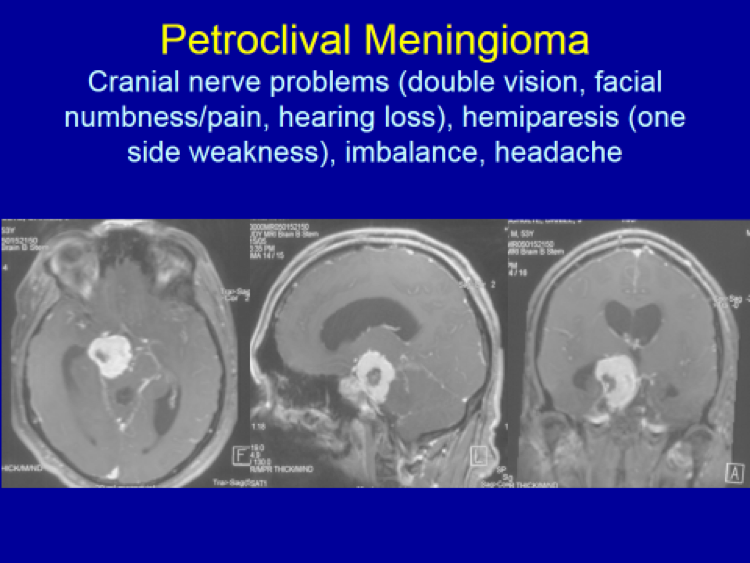

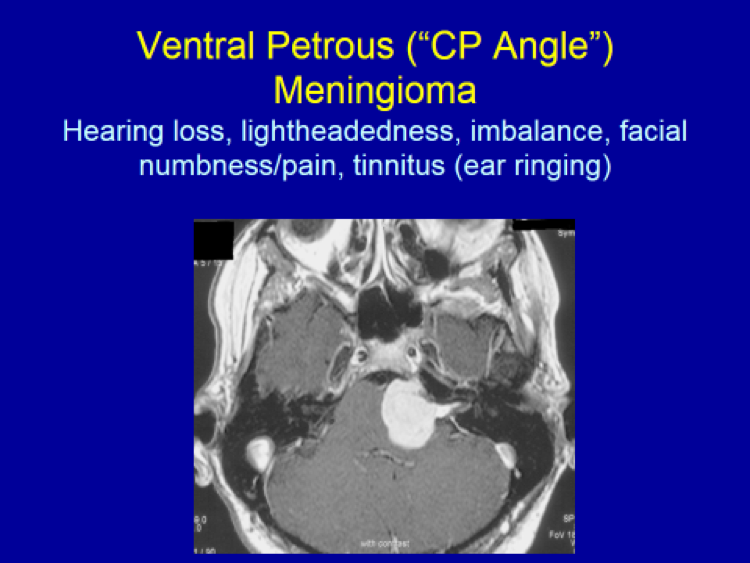

Please see the next section, “Clinical Presentation/Meningiomas by Location”, for examples of meningioma MR images.